Foreword

Data Point 1: The number of people heading out for hikes is growing. In the Seattle area, for instance, recent reports have the number of hikers increasing seven times faster than the population. Authorities credited (or blamed) social media! It seems hikers are 43 percent more likely to have used Instagram in the last thirty days.

Data Point 2: Increased visitation leads to sanitation problems. In the High Peaks of the Adirondacks, for instance, “staff come upon people in the midst of pooping on the trails,” says Julia Goren, education director for the local mountain club. Officials were defining it (nonironically, apparently) as “the number one stewardship issue” for the biggest state park in the country.

Data Point 3: When official systems dealing with human waste evaporate for even a few days—say, when the president of the United States throws a tantrum and closes the government—chaos reigns: the government shutdown at the start of 2019 resulted in myriad reports of the composting toilets in national parks overflowing. “Appalling,” one official put it.

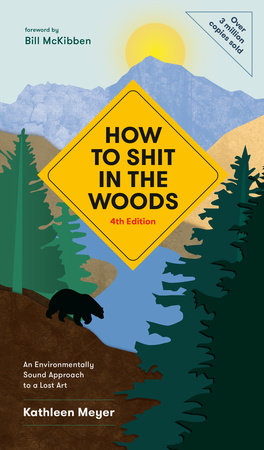

All of which is to say, thank heaven that Kathleen Meyer’s publisher is sending her classic out into the world again. It provides the same great service it did upon its original publication in 1989 (back in the days when the title was actually kind of shocking). The learning curve for us is easy—this is not like studying to play the violin or speak Mandarin. We emerge from it better, more resourceful, people more able to deal with the modern vicissitudes of life.

Read it as a guide but also as a metaphor. I published a book in 1989 too,

The End of Nature, which was the first book for a general audience about global warming or, as we called it then, “the greenhouse effect.” In the intervening few decades, we have endlessly poured more carbon into the atmosphere, heating the earth. We have, as it were, a big waste problem. We’re turning the planet into a dump—as Pope Francis put it in his remarkable encyclical

Laudato Si, “The earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth.”

So when you’re squatting in the bushes, too busy to sneak a peek at Twitter, take the moment to consider how what you’re learning in these pages might, in parallel, apply to the even greater problems that threaten our lovely home. This volume is immensely practical, in deep and powerful ways.

—

Bill McKibben, author of

Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?Preface

In response to Nature’s varied calls,

How to Shit in the Woods presents a collection of techniques (stumbled upon by the author, usually in a most graceless fashion) to assist the latest generation of backwoods enthusiasts still fumbling with their drawers. Just as important is the intention to answer a different and more desperate cry, from Nature herself, by conveying essential, explicit environmental precautions about wilderness toilet habits—applicable to a variety of seasons and climates and terrains.

For many millennia our ancestors successfully squatted in the woods. You might think it would come by instinct, nature simply taking its course when a colon is bulging or a bladder bursting. But “its course,” I cheerlessly and laboriously discovered, is subject to infinite disastrous destinations.

Years of guiding city folks down whitewater rivers sharpened my squatting skills and assured me I wasn’t alone in the klutz department. Frequently, the strife and anxiety experienced in the bushes were more intense than any sweat produced by the down-stream roar of a monster, raft-eating rapid. Those river days led me to a couple of firm conclusions. One: Monster rapids inspire a lot of squatting, which in turn supports a wealth of study material for two. Two (ultimately one of the subjects that prompted this publication): Finesse at shitting in the woods—or anywhere else outdoors—is not come by instinctively. That might sound as though I were a regular Peeping Joan. But with several dozen bodies squatting behind the few bushes and boulders of a narrow river canyon, I found it practically impossible not to trip over a few—exhibiting all manner of contorted expressions and positions—every day. Generally, a city-bred adult can expect to be no more successful than a tottering one-year-old in dropping his or her pants to squat. Shitting in the woods is an acquired rather than innate skill, a skill honed only by practice, a skill all but lost to the bulk of the population along with the art of making soap, carding wool, and skinning buffalo.

We are now many generations potty-trained on indoor plumbing and accustomed to our privacy, comfort, and convenience. To a person raised with a spiffy, silenced, flush toilet, sequestered behind a bolted bathroom door, having to go in the backcountry can rapidly degenerate into a frightening physical hazard, an embarrassing mess, or, incredibly, a weeklong attack of avoidance constipation.

A lust for wilderness vacations and exotic treks keeps exploding out of our metropolitan confines. As victims of urban madness, we fervently seek respite in the wilds. Masses of bodies thunder through forests, scurry up mountain peaks, flail down rivers, and, without serious attention on our part, leave a wake of toilet paper and fecal matter that Mother Nature cannot fathom. It’s not unrealistic to fear that within a few more years the last remaining pristine places could well exhibit conditions equal to the world’s worst slums.

Anyone who has come upon a favorite, once-lovely beach, camp, or mountain lake trashed by the likes of soiled toilet paper, baby diapers, and raw turds understands the horror. But greater than the visual impact of human toilet trash are the veiled environmental consequences. No longer can we drink from even the most remote, crystal clear streams without the possibility of contracting diseases.

And once the “authorities” step in and take over preservation, it is, to my mind, already too late. Rules and regulations imposed by government agencies (now absolutely necessary in many areas) can themselves be rude incursions on majestically primitive surroundings and antipodal to the freedom wildness represents. Rules, signs, application forms, and their ensuing costs are truly a pain in the ass, brought about not solely by increased numbers of people, but also by the innocently unaware and the blatantly irresponsible. It is to these sacred, wild havens that we journey to heal and revitalize. We cherish what they deliver in high challenge, copious physical sweating, magnificent exhilaration, and the divine gifts of quietude and profound wonder. With our lives under incessant assault from modern-day stresses and crises—from just plain existing to all out planet-saving—the stakes for caretaking our wildlands turn evermore crucial. A willingness to

inspire preservation comes most naturally from those who delight in the untrammeled wilds; it is they—we—who have the greatest responsibility to generate respect, care, and education. It is we who must learn and teach others how and where to shit in the woods.

Copyright © 2020 by Kathleen Meyer. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.