Introduction

I last spoke to Prince on Sunday, April 17, 2016, four days before he died. That night I was lying in bed when my phone shuddered and lit up with a 952 area code. He’d never called my cell before, but I knew at once it was him. I scrambled for a pen and paper and plugged my phone into the wall—my battery was almost depleted. But my charging cord was only a foot long, so I couldn’t stand up when I used the phone. I spent our final conversation hunched in the corner of my bedroom, taking notes by pressing the paper to the floor.

“Hi, Dan,” he said, “it’s Prince.” Much has been written about Prince’s speaking voice—the strange whispery fullness of it, reedy but low. Nowhere was this paradox more apparent than in that simple introduction: “Hi, Dan, it’s Prince.” He always used it. “I wanted to say that I’m alright,” he said, “despite what the press would have you believe. They have to exaggerate everything, you know.”

I had some idea. In the month since Prince had announced that “my brother Dan” was helping him work on his memoir, I’d seen it reported that I—twenty-eight years his junior, and white—was literally his brother. But the news now was of another order of magnitude. A few days earlier, Prince’s plane had made an emergency landing after departing Atlanta, where he’d just finished what would be his final performance, part of a searching, contemplative solo tour he called “Piano & A Microphone.” He’d been hospitalized in Moline, Illinois, supposedly to treat a resilient case of the flu.

Within hours of the story breaking on TMZ, Prince had tweeted from Paisley Park, in Chanhassen, Minnesota, saying that he was listening to his song “Controversy”—which begins, “I just can’t believe all the things people say.” Subtext: He was fine. Some residents of Chanhassen had seen him riding his bicycle. And the night before he called me, he’d thrown a dance party on his private soundstage, using the opportunity to show off a new purple guitar and a purple piano. “Wait a few days before you waste any prayers,” he’d told the crowd.

“I was worried, but I saw on Twitter that you were okay,” I told him. “I was sorry to hear you had the flu.”

“I had flu-like symptoms,” he said—a clarification that I’d dwell on a lot in the months to come. “And my voice was raspy.” It still sounded that way to me, as if he was recovering from a severe cold. But he didn’t want to linger on the subject. He’d called to talk about the book.

“I wanted to ask: Do you believe in cellular memory?” He was speaking of the idea that our bodies inherit our parents’ memories—that experience is hereditary. “I was thinking about it because of reading the Bible,” he explained. “The sins of the father. How is that possible without cellular memory?”

The concept resonated in his own life, too. “My father had two families. I was his second, and he wanted to do better with me than with his first son. So he was very orderly, but my mother didn’t like that. She liked spontaneity and excitement.”

Prince wanted to explain how he emerged as the synthesis of his parents. Their conflict lived within him. In their discord, he heard a strange harmony that inspired him to create. He was full of awe and insight about his mother and father, about the way he embodied their union and disunion.

“One of my life’s dilemmas has been looking at this,” he told me as I sat on my floor, scribbling away. “I like order, finality, and truth. But if I’m out at a fancy dinner party or something, and the DJ puts on something funky . . .”

“You’ll have to dance,” I said.

“Right. Like, listen to this.” He held the phone up to a studio monitor and played a few bars of something that sounded boisterous, brassy, and earthy, like a house party from many decades ago. “It’s funky, right? That’s from Judith Hill’s new album. It’s the first time I’m hearing it.”

He paused for a moment. “We need to find a word,” he said, “for what funk is.”

The quest for that word was never far from Prince’s mind in those days. His asides to the crowds at his Piano & A Microphone shows often found him reflecting on the rudiments of funk. “The space in between the notes—that’s the good part,” he would say. “However long the space is—that’s how funky it is. Or how funky it ain’t.” Unpacking these ideas is part of what made him want to write a book in the first place.

Though Prince had published several photo books, and though he’d entertained the notion of something more substantial at various points in his career, the genesis of this project came in late 2014, when his manager and attorney, Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins, sought out a literary agent to represent him. Prince chose Esther Newberg, of the talent agency ICM Partners. She represented his friend Harry Belafonte, and he liked her old-school sensibility—plus, she appealed to him as a matriarch in a patriarchal industry. By early 2015, Prince had signed off on a concept, a book of lyrics with his own introduction and annotations. Newberg and her colleague Dan Kirschen shopped the idea to eager publishers, but Prince’s camp never finalized a deal, and for most of 2015 he focused on music.

In mid-November, he turned to the book with renewed enthusiasm. “He would like to fast-track a project,” Ellis-Lamkins wrote to Newberg. Working with Trevor Guy, an aide who helped with business affairs, Prince, Esther, and Dan expanded the book’s nebulous purview. What if it included not just annotated lyrics but unpublished sketches, photos, and ephemera? The word memoir wasn’t part of the conversation yet, but Prince wanted to begin work on the project right away. Trevor suggested convening a group of editors at Paisley Park to discuss it in person.

The book coincided with an inward turn in Prince’s music-making. Having traveled the world in recent years with his electrifying band 3RDEYEGIRL, he was electing to play alone now. He envisioned a tour comprising just him and his piano. The intimate, amorphous sets would span his career without the constraints and pyrotechnics of an arena show. Hosting a group of European journalists at Paisley Park, he explained that he relished the thrill of taking the stage unadorned, paring his songs down to their essential components and reinventing them on the fly. He’d been practicing into the night, playing alone for hours on end, his piano filling the vast darkness of his soundstage until he found something that he described as “transcendence.” This was what he wanted to share.

He’d booked dates across Europe when terrorists in Paris attacked the Bataclan, a concert hall he’d played three times. The violence, combined with price gouging by ticket resellers, convinced him to scuttle the tour. Why not just host the shows at Paisley Park? On his home turf, he could mount a production befitting the price.

As Prince’s vision for Piano & A Microphone found clarity, his book began to take shape, too. According to one friend, several of the people he loved and admired were falling ill, making him conscious of his own mortality. More than ever, he saw the value in telling his own story. On January 11, 2016, a few weeks before he gave his first solo performance, he invited three editors to meet with him at Paisley Park, where he’d explain his ambitions and decide which publishing house he wanted to work with. A meeting with multiple competing editors at the same time was an atypical arrangement. And then there were all the rumors they’d heard: Didn’t he bristle at questions about his past? Would he eject anyone who used profanity, or demand a contribution to his swear jar? Was it true you weren’t allowed to look him in the eye?

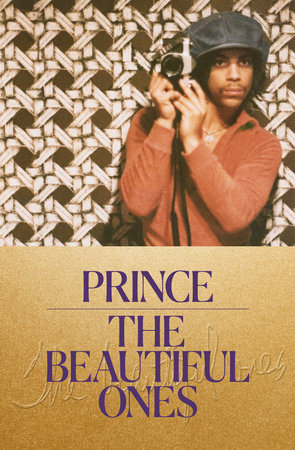

As soon as Prince walked into the meeting, any sense of trepidation dissolved. He was charming, engaged, even self-deprecating. (“I ramble sometimes,” he said.) For the next two hours, he presided over a freewheeling discussion of his past, his musical philosophy, and his aspirations for the book. He wanted to write a memoir, he declared—a decision he’d arrived at so recently that even Trevor, who sat in on the meeting, was surprised by it. It would be called

The Beautiful Ones, after one of the most naked, aching songs in his catalog.

The story would focus on his mother, whose gaze was “the first I ever saw,” and who had never received proper credit for her role in his success. He shared an assortment of objects with the assembled editors. He’d asked his sister Tyka to send him old family photos, including many of his parents, and a family tree. He’d also tracked down the original cover art for

1999, a collage ornamented with cutouts of a phone booth, a futuristic skyline, and a nude woman with a horse’s head. And he presented the first iteration of a screenplay,

Dreams, that would become

Purple Rain.

Copyright © 2019 by Prince. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.