Introduction Mushrooms are the reproductive structures or "fruit" of certain fungi. The most familiar kind of mushroom has a cap with

gills (radiating blades) on its underside. Millions of microscopic reproductive units called

spores are discharged from the gills and dispersed by air currents. Only a small percentage of spores land in a favorable environment, where they germinate to form new fungi.

Fungi do not manufacture their own food like plants. In this respect they are like animals: they must obtain food from outside sources. The part of the mushroom fungus that digests nutrients is an intricate web of fine threads collectively called the

mycelium (plural: mycelia). The mycelium may live anywhere from a few days (in perishable substrates like dung) to several hundred years, periodically producing mushrooms when enough moisture is available.

Mushrooms, or more exactly the fungi that produce them, are a vital and omnipresent part of our environment. Despite their bad press, the overwhelming majority are beneficial. A few are

parasitic, feeding on living organisms, usually trees. The rest are either saprophytic or mycorrhizal.

Saprophytic fungi are nature's recyclers. They replenish the soil by breaking down complex organic matter (wood, dung, humus, etc.) into simpler, reusable compounds.

Mycorrhizal fungi form a mutually beneficial relationship with the rootlets of plants in which nutrients are exchanged. They are critical to the health of our forests, as many trees will not grow without them. (Since some mycorrhizal mushrooms are associated with certain kinds of trees, make a habit of noting the different trees growing in the vicinity of any mushroom you wish to identify.)

Despite the many benefits and uses of mushrooms, most North Americans are markedly

fungophobic, a trait inherited from the British. Fungophobia can be defined as the belief that mushrooms are actively hostile at worst and worthless at best. It is only in the last few years that large numbers of North Americans have begun to discover what the mushroom-loving peoples of Japan, China, Russia, and Europe have known for centuries: that these "forbidden fruit" are delicious and nutritious, vital and valuable, potent and beautiful, and that mushroom hunting is a challenging, enlightening, and uplifting activity.

How To Use This Book Simple. Once you've collected a distinctive mushroom, consult the quick key to mushroom groups on the inside front and back covers, and go to the section of the book indicated. Flip through the pictures in that section until you find one that looks similar to your mushroom. Then carefully go through the numbered list of "Key Features" on that page, checking them off as you go so you don't inadvertently miss one. If your mushroom has

all of the key features, then you have identified it! To verify your identification, check the details listed under "Other Features," "Where," etc.

If your mushroom does not agree with one of the "Key Features," assume it is different. First consult the section called "Note" at the bottom of the page for a possible explanation of the discrepancy or a listing of similar species, then continue searching the pictures for another likely candidate. If you can't find a photograph and set of key features that match your mushroom, there are two possible explanations.

The first is that your mushroom is a "freak"—an untypical example of an illustrated species, for instance one that has faded badly or lost its ring. By collecting

several examples of each kind of mushroom you wish to identify, in different stages of development if possible, you are much more likely to gather at least a few typical, identifiable ones; then you can discard those that lack one or more of the key features unless you are experienced enough to recognize them. (Note: different kinds of mushrooms often mingle with one another; unless they are obviously the same, assume that they are different until you discover otherwise.)

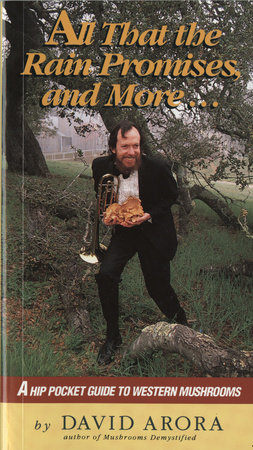

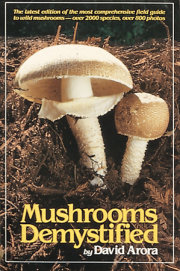

The second, and more likely, explanation is that your mushroom is not in this book. After all, less than 10 percent of the known species from western North America are. You can return unidentified mushrooms to their place of origin, relegate them to the compost pile, or, if you are determined to know their identity, consult a more comprehensive guide such as

Mushrooms Demystified, 2d ed. (1986).

Copyright © 1991 by David Arora. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.