Introduction

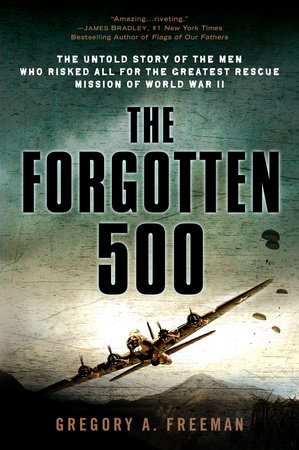

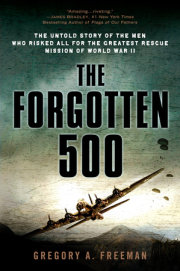

One of the last untold stories of World War II is also one of the greatest. It’s a story of adventure, daring, danger, and heroics followed by a web of conspiracy, lies, and cover-up.

The story of Operation Halyard, the rescue of 512 Allied airmen trapped behind enemy lines, is one of the greatest rescue and escape stories ever, but almost no one has heard about it. And that is by design. The U.S., British, and Yugoslav governments hid details of this story for decades, purposefully denying credit to the heroic rescuers and the foreign ally who gave his life to help Allied airmen as they were hunted down by Nazis in the hills of Yugoslavia.

Operation Halyard was the largest rescue ever of downed American airmen and one of the largest such operations in the war or since. Hundreds of U.S. airmen were rescued, along with some from other countries, right under the noses of the Germans and mostly in broad daylight. The mission was a complete success, the kind that should have been trumpeted in newsreels and published on the front page of the newspapers. But it wasn’t.

It is a little-known episode that started with one edge-of-your-seat rescue in August 1944, followed by a series of additional rescues over several months. American agents from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor of the CIA, worked with a Serbian guerilla, General Draza Mihailovich, to carry out the huge, ultrasecret rescue mission.

These are the tales of young airmen shot down in the hills of Yugoslavia during bombing runs and the four secret agents who conducted their amazing rescue. These are the stories of young men—many of them first-generation Americans, the proud, patriotic sons of European immigrants—who were eager to join the war and fight the Germans, even finding excitement in the often deadly trips from Italy to bomb German oil fields in Romania, but who found themselves parachuting out of crippled planes and into the arms of strange, rough-looking villagers in a country they knew nothing about. They soon found that the local Serbs were willing to sacrifice their own lives to keep the downed airmen out of German hands, but they still wondered if anyone was coming for them or if they would spend the rest of the war hiding from German patrols and barely surviving on goats’ milk and bread baked with hay to make it more filling.

When the OSS in Italy heard of the stranded airmen, the agents began to plan an elaborate and previously unheard-of rescue—the Americans would send in a fleet of C-47 cargo planes to land in the hills of Yugoslavia, behind enemy lines, to pluck out hundreds of airmen. It was audacious and risky beyond belief, but there was no other way to get those boys out of German territory. The list of challenges and potential problems seemed never ending: The airmen had to evade capture until the rescue could be organized; they had to build an airstrip large enough for C-47s without any tools and without the Germans finding out; then the planes had to make it in and out without being shot down.

The setting for this dramatic chapter in history is a region that, for modern-day Americans, has become synonymous with brutal civil war, sectarian violence, and atrocities carried out in the name of ethnic cleansing—an impression that, though it may ignore the region’s rich cultural history, is not inaccurate. Serbia covers the central part of the Balkan Peninsula, also known as the Balkans, a region in southern Europe separated from Italy by the Adriatic Sea. Serbia borders Hungary to the north; Romania and Bulgaria to the east; Albania and the Republic of Macedonia to the south; and Montenegro, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west.

Throughout history the area has been neighbor to great empires, a proximity that contributed to a rich mixture of ethnicities and cultures, but also to a long history dominated by wars and clashes between rival groups of the same country. The fractious nature of the region even led to the term “Balkanization” or “Balkanizing” as a shorthand for splintering into rival political entities, usually through violence. The word “Balkan” itself is commonly used to imply religious strife and civil war.

The former Yugoslavia is a region seemingly in a constant state of flux. During World War II, Serbia was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which then became the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1945. In 1992 the country was renamed the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, then the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro from 2003 to 2006. When Montenegro voted independence from the State Union, Serbia officially proclaimed its independence on June 5, 2006.

Serbian borders and regions are determined largely by natural formations, including the Carpathian Mountains and the Balkan Mountains, which create the mountainous region that formed a hurdle for crippled American bombers trying to return to their bases in Italy, but which also sheltered downed fliers from the German patrols hunting them.

From the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria at Sarajevo, which set off World War I, to the Nazi occupation in World War II, the region was in the center of global conflicts while contending with its own internal strife. The former Yugoslavia is a mix of different ethnic and religious groups, including Serbs, Croats, Muslims, and Slo- venes. Throughout history, ancient and recent, most of the fighting in the region has been a struggle among these groups for the control of territory. After World War II, the Bosnian Muslims were strong supporters of Communist leader Josip Broz Tito, partly because he was successful at keeping the ethnic groups peaceful—just as Italian dictator Benito Mussolini made the trains run on time. Serbs were the most populous ethnic group in the former Yugoslavia, with a national identity rooted in the Serbian Orthodox Church.

After World War I, the Serb monarchy dominated the new nation of Yugoslavia. During World War II, hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews, and Gypsies were killed by Croat Fascists, called Ustashe, and by Germans. Some Muslims fought for the Nazis, while many other Muslims and Croats fought for the Partisans led by Tito. Serbs supported the exiled royal government.

These age-old hatreds and ethnic disputes erupted in 1992 to cause the bloodiest fighting on European soil since World War II. More than two hundred thousand people, most of them civilians, were killed and millions more were left homeless. As the fighting raged and the world learned of atrocities committed against civilian populations simply for being of the wrong ethnic background, European nations responded with numerous peace proposals that produced no peace. Then the United States moderated peace talks at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio. The talks led to a November 21, 1995, peace accord that relied on sixty thousand NATO troops to stop the killing.

The Bosnian war of the 1990s was particularly vicious. While Serbs are generally considered the aggressors in the Bosnian conflict of the 1990s, there also are legitimate charges that Croats and Muslims operated prison camps and committed war crimes. Some critics accused former Bosnian president Alija Izetbegovic of looking the other way while his Muslim soldiers committed war crimes in retaliation against Serb attacks. Many Serbs acknowledge the well-documented atrocities committed by Bosnian Serb militia against Muslim and Croat civilians, but they also argue that Serb civilians were the victims of similar crimes and that the Western media coverage was skewed by a bias in favor of the Muslim and Croat sides.

The Dayton accord did not completely end the violence in the region. Between 1998 and 1999, continued clashes in Kosovo, a province in southern Serbia, between Serbian and Yugoslav security forces and the Kosovo Liberation Army prompted a NATO aerial bombardment that lasted for seventy-eight days. The peace among Serbs, Croats, and Muslims in the area of the former Yugoslavia still is a fragile one.

American fliers who parachuted out of their bombers over Yugoslavia in World War II had little idea of the complex, troubled history of the country in which they were about to land, or of the international disputes in which they were about to become entangled. They sought refuge and a way back home, and they were humbled by the outpouring of support from the poor Serb villagers who risked their own lives to help the Americans drifting down out of the sky.

As the world came to know only the modern-day violence of the Bosnian wars, there was a small band of men who knew that the people in that distant country had once done a great service to the American people and to many young men who were scared, tired, and hungry. They held on to that story and told everyone they knew, yet the story slowly died with the forgotten 500.

Only a handful of the rescued airmen and OSS agents are still alive to tell the stories, their health and memories fading fast. But they insist that the world know the truth of what happened in Yugoslavia in 1944, including the series of almost unbelievable coincidences and near misses—everything from an improbable meeting with a top Nazi officer’s wife to a herd of cows that show up at just the right moment—that made their rescue possible.

They never forgot, and they refuse to let the story die with them.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.