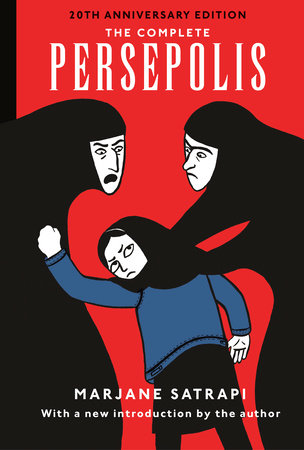

INTRODUCTION

To the 20th Anniversary Edition

When

Persepolis was first published in France in 2000, I was sure the world was headed in the right direction. There were no major wars, and it seemed that humanity had somehow learned from its mistakes, that in the twenty-first century we’d finally come to realize that the earth belonged to everyone equally and that we were one race—the human race.

Believing this, I was certain the need for the book would fade over time. That soon enough what I had written about—living through a revolution and a war and growing up under the Islamic Republic of Iran’s dictatorship—would feel like ancient history. Unfortunately, I was wrong.

Persepolis was released in the United States in 2003, in the aftermath of 9/11, and we Iranians had come to be considered part of the Axis of Evil. I was invited to appear across the country, even at West Point, where I spoke about the importance of differentiating between the Iranian people and the actions of the Islamic Republic, and I became a vocal critic of the war in Iraq, pointing out the hypocrisy of trying to instill democracy with bombs.

In the years since, the book has been both beloved and banned. Banned for its sexual scenes (I still don’t know where those scenes are); for its torture scenes (because it’s acceptable for assault rifles to be legal in the United States, even if that frequently results in the murder of innocent people, but it’s not okay for a reader to see a single drawing documenting the torture of political prisoners); and, more recently, because of Islamophobia.

I take the book’s banning as a huge compliment. A banned book is always a good book. After all, what better company to be in than Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain?

Now, as I write this, a new revolution is happening in Iran, started by young women in response to the killing of Mahsa Amini. It’s the first feminist revolution in which women and men are fighting together, hand in hand for their freedom.

I am certain we will succeed.

Why am I hopeful?

First off, at the time of the 1979 revolution that I describe in

Persepolis, only 40 percent of Iranians were literate; today more than 80 percent are. Second, the digital revolution has allowed an entire generation unfettered access to information, to be in touch with the world and to decide for themselves what they want to believe in. Third, a dictatorship that is ready to accept reform is no longer a dictatorship. And, finally, the future of every country is its youth, and this new generation is modern, not sexist, and aspires to freedom and democracy. Moreover, they did not have to live through the trauma of revolution and war the way we did.

No country in the world has had as many revolutions as Iran. But this time the youth are not just educated; they are fearless in their opposition to gender apartheid and patriarchal culture, which are the biggest enemies of democracy. Not only has the wall of fear fallen but fear has changed sides.

The young Marji I was would certainly not leave her country; she would surely stay and fight, but at the time I wrote this book she couldn’t. Reading

Persepolis today, it’s clear how little the situation has changed—it’s people’s reactions that have evolved. Instead of running away from the bully, we fight.

At the end of the book’s original introduction, I wrote: “One can forgive but should never forget.” Twenty years later I would add: One also has to understand why this happened. Because if we know the answer, we can stop history from repeating itself.

To the freedom of all, wherever they may be.

Marjane Satrapi

Paris, 2023

Copyright © 2023 by Marjane Satrapi. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.